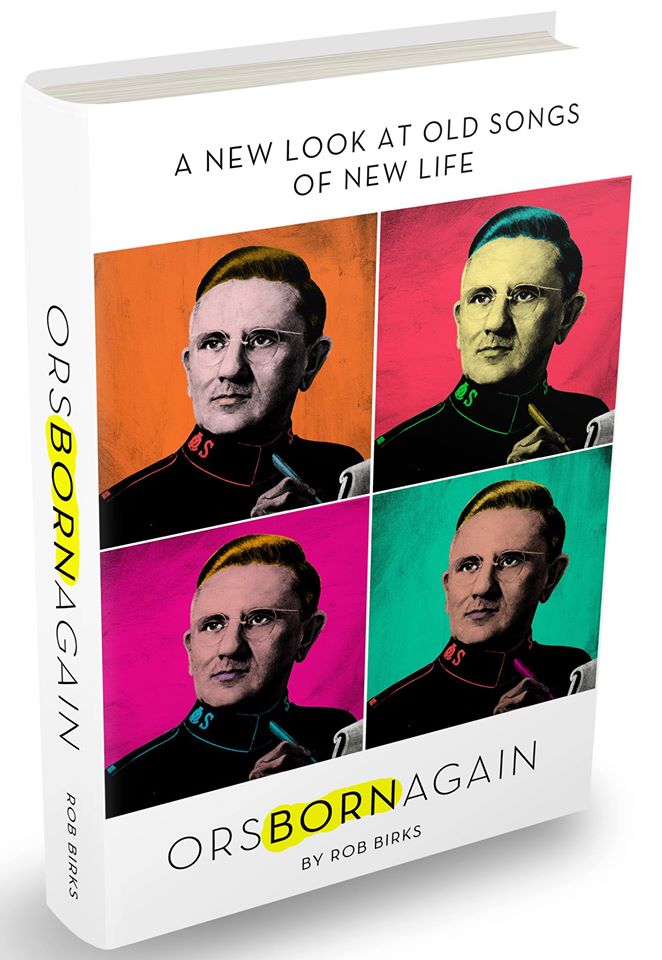

ORSBORNAGAIN (10)

A devotional series by Major Rob Birks

ORSBORNAGAIN is meant to introduce the poetry of the first Poet General, Albert Orsborn (1886-1967) to a new audience and to reintroduce his works to dyed-in-the-(tropical)-wool Salvationists.

These are not new songs.

However, the lyrics are jam-packed with new life, which may be missed during corporate worship. Re-examined through scripture and experience, Rob Birks intends through an examination of these scared songs to renew the spiritual fervor of believers, and point seekers to their Savior.

I have no claim on grace;

I have no right to plead;

I stand before my maker’s face

Condemned in thought and deed.

But since there died a Lamb

Who, guiltless, my guilt bore,

I lay fast hold on Jesus’ name,

And sin is mine no more.

From whence my soul’s distress

But from the hold of sin?

And whence my hope of righteousness

But from thy grace within?

I speak to thee my need

And tell my true complaint;

Thou only canst convert indeed

A sinner to a saint.

O pardon-speaking blood!

O soul-renewing grace!

Through Christ I know the love of God

And see the Father’s face.

I now set forth thy praise,

Thy loyal servant I,

And gladly dedicate my days

My God to glorify.

Albert Orsborn

463 Our Response to God – Salvation, Forgiveness

When it’s sin versus grace, grace wins hands down (Rom. 5:20b MSG).

As I’m writing this, Stacy is in London finishing eight weeks of study and spiritual renewal at The Salvation Army’s International College for Officers. A few nights ago, thanks to a generous gift from an old friend, she was able to see Les Misérables on stage with a new friend. Yesterday, coincidentally, a friend of mine posted the trailer for the new film version of the musical. By the time this is read, we will all have our own opinions on whether or not the film honored the beauty of the stage production, and how it compared to the 1998 movie with Liam Neeson, Uma Thurman and Geoffrey Rush.

I remember receiving the novel as a gift one Christmas, and reading it in just about 24 hours (and it’s not a Grisham-length tale). There’s just something about that story that resonates in me. The same year that the non-musical movie version of Les Misérables was released, the modern classic book What’s So Amazing About Grace? by Philip Yancey was published. In that book I discovered, among many other things, the reason Victor Hugo’s story is so compelling to me: GRACE! (Yes, I am yelling, but in a good way.)

There are many depictions of grace in the novel and screenplay, but one of the scenes Yancey points to is the one that has stuck with me ever since. After he wandered the village roads for four days, looking for lodging, ex-con Jean Valjean was given food and shelter by a bishop. That night, while the bishop slept, Valjean ran off, but not before he took the household silver. The next morning, the police are at the bishop’s door. They had captured the convict. All it would take was a word from the bishop, and Valjean would go back to prison and hard labor. The bishop gave a word alright, but it wasn’t the one the police, or Valjean, or the reader was expecting:

“So here you are!” he cried to Val Jean. “I’m delighted to see you. Had you forgotten I gave you the candlesticks as well? They’re silver like the rest, and worth a good 200 francs. Did you forget to take them?”

The bishop then told the police, “The silver was my gift to him.” In the musical version, during the song “What Have I Done,” the bishop sings these words to Jean Valjean: “You forgot I gave these also. / Would you leave the best behind?” Grace and more grace! In the novel, the movie and the musical, Valjean can’t believe his ears. He was captured. He was guilty. He was on his way back to prison. Now he was free. He was declared innocent. He was on his way to make something meaningful of his life. Thanks to the bishop, Valjean hadn’t left the best behind. But he had, thanks also to the bishop, left the worst behind – for good.

Grace is found in all three verses of the work of Orsborn’s art that we are considering here. Actually, grace can be found in all of his writings, but here he names it. Grace. Grace. Grace. He had “no claim” on it. He knew his “hope of righteousness” was found in it. And he had experienced its “soul-renewing” power. Like Jean Valjean, Orsborn knew himself to be “condemned in thought and deed.” And like Orsborn, Valjean was forgiven and set free by the one against whom he had sinned.

Here’s the bad news. We, all of us, after sneaking off in the middle of the night with something that isn’t ours, have been caught red handed. We, all of us, deserve to be convicted and sentenced, not just to a life of imprisonment, but to death. Here’s the good news. We, all of us, have a Savior who, guiltless, our guilt bore. We, all of us, can speak to him our needs, and tell our true complaint. And we, all of us, can be converted from “a sinner to a saint.”

Here’s one more thing that faithful Orsborn and fictional Valjean had in common. Neither of them forgot the moment they were graced, but made it a way of life.

I now set forth thy praise,

Thy loyal servant I,

And gladly dedicate my days

My God to glorify.